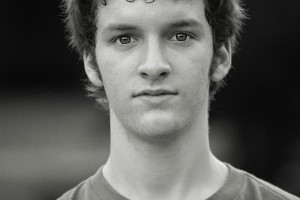

Erik Rune Medhus, my 20 year old son, took his own life on October 6, 2009. Since that sad and tragic day, an overwhelming sense of grief and despair propelled me into a search for answers. Answers that would provide me and others with comfort and hope. Some of those answers came from the many books I bought, but many came from an unexpected source…Erik, himself. Through dreams, visitations and channeling, he describes what happens during the death process, what the afterlife is like, what he does with his time there, what it feels like to be a free soul, the nature of thought and reality, the meaning of life and the human experience, as well as other matters. If you fear your own mortality, if you grieve over the loss of a loved one, or if you yearn to know the answers to these questions and more, please join me in this journey to enlightenment.

Erik Rune Medhus, my 20 year old son, took his own life on October 6, 2009. Since that sad and tragic day, an overwhelming sense of grief and despair propelled me into a search for answers. Answers that would provide me and others with comfort and hope. Some of those answers came from the many books I bought, but many came from an unexpected source…Erik, himself. Through dreams, visitations and channeling, he describes what happens during the death process, what the afterlife is like, what he does with his time there, what it feels like to be a free soul, the nature of thought and reality, the meaning of life and the human experience, as well as other matters. If you fear your own mortality, if you grieve over the loss of a loved one, or if you yearn to know the answers to these questions and more, please join me in this journey to enlightenment.

Erik would be the first to admit that he is no Oracle of Delphi. He does not claim to be a Dalai Lama, the Great Messiah, a mountaintop guru, or even a wise sage. No, he is a flawed human being who, like many of us, has battled his own dragons both inward and outward. He has stumbled and failed time and time again. But perhaps because of his foibles, he has a deep understanding of the human experience. He knows what it’s like to be neck deep in a foxhole of misery clawing desperately in the mud to pull himself out. He also knows what it’s like to feel hopelessness, to give up, to believe that life is not worth the pain, the trouble and the setbacks. But these attributes, these trials and tribulations offer another type of wisdom. One we can relate to in the shadow of our own hardships. That said, however young, flawed and imperfect, Erik is a voice worth hearing. He is one of us.

His Life and Death

Erik was born on September 21, 1989 at 3:00 in the afternoon. He greeted the world without a whimper. Instead of howls of protest at the bright lights and cool air, he seemed content to take in his surroundings peacefully. Until he was around 12 or 13, he was such a happy boy. He loved all things manly, motorcycles, military paraphernalia, race cars, and guns. He also adored women of all sorts. Even as a four year-old, he would lavish them with admiration and affection. Erik also loved dressing up in “Pappa suits,” and in the months before his death, he would often walk around in a suit and tie for no reason at all.

Erik had his struggles, though. He suffered from learning difficulties making school an unwelcome and often overwhelming undertaking. Despite our encouragement and understanding, his academic shortfalls ravaged his self-esteem. Peers and even some thoughtless teachers called him “stupid” to his face. To make matters worse, he also suffered from Tourettes, so his odd tics and mannerisms left him vulnerable to unkind remarks. It was during his middle school years that I began to see this happy, charming, affectionate child transform into a stranger. He slowly built a shell of toughness to protect himself from a cruel world. He wore spiked leather bracelets and long pocket chains, smiled less often and was involved in a number of fist fights at school.

Despite weekly sessions with both a therapist and a psychiatrist, Erik slid into a deep depression. He found solace in drugs and alcohol partly to give credence to that tough exterior, partly to ease the pain. As parents, we did everything we could to help him feel better about himself. As with all of our children, not a day would go by that we didn’t tell him how much we loved him and how grateful we were to have him in our lives.

After finally being diagnosed with and receiving treatment for Bipolar Disease, Erik seemed to improve somewhat. He stopped the drugs and alcohol and embarked on a career path to becoming a welder. But as happiness seemed to elude him still, he developed an insatiable appetite for material possessions to fill the empty void: a stereo system for his truck, a new welder, equipment for a new sport or hobby, or a new bike. When he ran out of money, he pawned nearly all of his other possessions for the next “fix.” He also had an intense yearning for friendships. Sadly, he was well aware of the fact that many of his “friends” answered his calls only to hang up immediately once they realized it was him. He was regarded as odd and quirky by many and, as a result, he often felt deeply lonely. I find this so ironic, because Erik was so caring toward others whether they were friends, acquaintances or strangers. He wouldn’t hesitate to give anyone the shirt off his back and often brought home troubled strays in need of a home cooked meal and a place to sleep. In all of his twenty years here on Earth, I have never heard him utter a critical or disparaging word about another person. Perhaps because of his struggles, he was one of the most compassionate, nonjudgmental people I have ever known.

Then came that horrible Tuesday, that deep chasm that tore my life into two parts, the “before” and the “after.” Erik seemed to be stable and happy that day. Those last few months, he had finally found friends he could trust, friends that loved him as he loved them. My sister, Teri, was visiting from her home in California and she, two of my daughters and I planned to go out somewhere for lunch. I asked Erik if he’d like to join us, but he declined, saying he preferred to stay home and “chill.” He asked how long we’d be gone, and I told him we’d return in no more than an hour. Five minutes into the drive I received the worst phone call of my life. Maria, our housekeeper who had helped take care of Erik since he was 16 months old, said she heard a “loud noise” and was scared. Although I had no reason to suspect anything, I instinctively knew. I asked her if it sounded like a gun and she replied, “yes.” I begged her to go upstairs to check on Erik and she did. The bloodcurdling scream I heard moments later will forever be etched in my mind–a scream that marked the beginning of a nightmare from which we would never awaken, a scream that dashed our hopes along with our sense of inviolability. It marked the beginning of our emotional collapse into a car full of hysterical sobs. We were home in a matter of minutes, minutes that seemed more like decades. I was so afraid to go upstairs and confront what I knew to be the tragic truth, but as a physician, I needed to be sure he was truly dead. What if he still had a pulse? Maybe I could administer CPR and save him. But upon seeing my son sitting in his desk chair, eyes opened and lifeless, with an obvious gunshot wound to the head, it was clear he was gone forever and could not be brought back to life. Only days later would I discover that he had pawned other possessions and asked a 21 year-old friend to purchase a handgun. In great despair, I flung myself into his lap, screaming like a wounded mother wolf mourning the loss of her cub. It felt like I was out of my body peering down upon this broken shell of a woman whose hands were bathed in the blood of her own child.

The moments and months that followed were torture. No mother should have to bury her child, much less hired a crime scene cleanup crew to pull out his carpet and scour the walls. Since that day, every chore seems overwhelming whether going out to get the mail or unloading the dishwasher. But even as early as the next morning, Erik came to comfort us in many ways, as you will see.